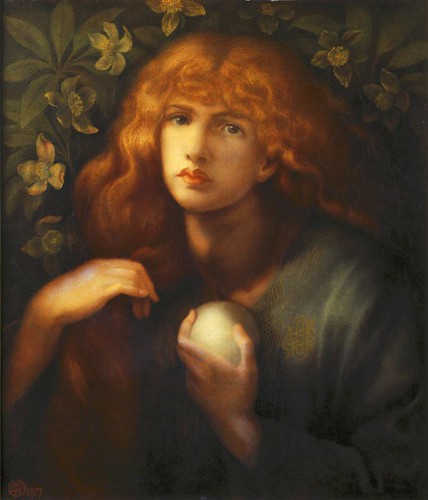

Alexa Wilding, 1877, Dante Rossetti

“A woman, generally single, or in some way not in a condition for performing her reproductive function, having suffered from some real or imagined trouble, or having passed through a phase of hypochondriasis of sexual character, and often being of a highly nervous stock, becomes the interesting invalid. She is surrounded by good and generally religious and sympathetic friends. She is pampered in every way. She may have lost her voice or the power of a limb. These temporary paralyses often pass of suddenly with a new doctor or a new drug; but, as a rule, they are replaced by some new neurosis. In the end, the patient becomes bedridden, often refuses her food, or is capricious about it, taking strange things at odd times, or pretending to starve. Masturbation is not uncommon. The body wastes, and the face has a thin anxious look, not unlike that represented by Rossetti in many of his pictures of women. There is a hungry look about them which is striking.”

Dr. George Savage, Insanity and Allied Neuroses (1884)

Savage’s description of the female neurasthenic incorporates some of the sexual stereotypes of the hysteric. (Taken from Elaine Showalter, The Female Malady, 1987)

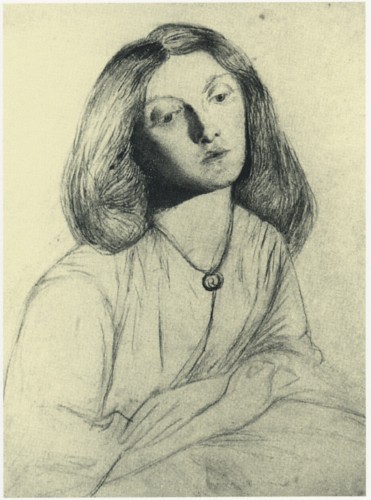

Sketch of Elizabeth Siddal, 1860, Dante Rossetti

Seated Elizabeth Siddal, c. 1861 (?), Dante Rossetti

Elizabeth Siddal plaiting her hair, c. 1861 (?), Dante Rossetti

As an undergrad, in my final year, for my history and art history joint major, I took a module called "Madness & Civilization". It was consistently fascinating, and the required reading list presented to me The Female Malady by Elaine Showalter. I was reading it on and off for months, underlining, bookmarking and dog earing many pages. One of the sections that really stuck with me was the one above. As a student of nineteenth-century art history, the association with the Pre-Raphaelites and their romaniticisation of what was generally considered a feminine illness (hysteria, derives from the Greek 'hystera'; womb) fascinated me. The languid subjects of Rossetti (and indeed the Pre Raphaelite's body of work) belies conventional interpretation.

Mary Magdalene, 1877, Dante Gabriel Rossetti

"There is a hungry look about them which is striking."

In an Artist's Studio, Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830-1894)

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel -- every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

This poem seems to be inspired by Christina’s observations of her brother’s relationship with Elizabeth Siddal, who is the focus of many of his paintings (and most particularly his sketches, as detailed above). In reading this poem above, and reading Dinah Roe's analysis, the artist, in common with the Victorian psychiatrist, his model (patient) is present at the mercy of his creativity. Their relationship is parasitic, the muse inspires thus supplying his art, and thence, pays his bills. Similarly for the psychiatrist, young women's (under the guise of anonymity) nervous conditions were interpreted as the (male) psychiatrist saw fit. This inclination can be seen in the case of Jean-Martin Charcot's photographs of female patients suffering from a variety of neuroses in Salpêtrière Psychiatric Hospital in Paris. Framing these works in a female-historical context, the romantic notion of "tragic beauties" takes on a new interpretation. Their feminine beauty is captured by the brush and pen, permanently recorded, but by the same stroke, this beauty is fleeting, it is the artist/psychiatrist who takes the credit for (literally and metaphorically) capturing their beauty. Their male creativity is celebrated, while the muse seems to lose their sense of self through this relationship, the ennui of their gender role (the expectation of the "Angel in the House") can be seen in the vacant expressions (sometimes described as "sensual") of the subjects above. Behind the romantic facade, for Elizabeth Siddal or in the cases of "Augustine" and "Dora", the consequence, or outcome, was total annihilation of self.

Elizabeth Siddal, 1860s, Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Elizabeth Siddal, 1860s, Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Some articles of interest...

Rossetti’s Other Women: The silent contribution of models and muses

-

Dinah Roe's analysis of Christina Rossetti's In an Artist's Studio (Part 2 of 3)

-

Curator Pamela Gerrish Nunn on the forgotten Pre-Raphaelite Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale

-

A Pre-Raphaelite Journey: Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale